Rabbi Steve Leder looks at how suffering transforms us.

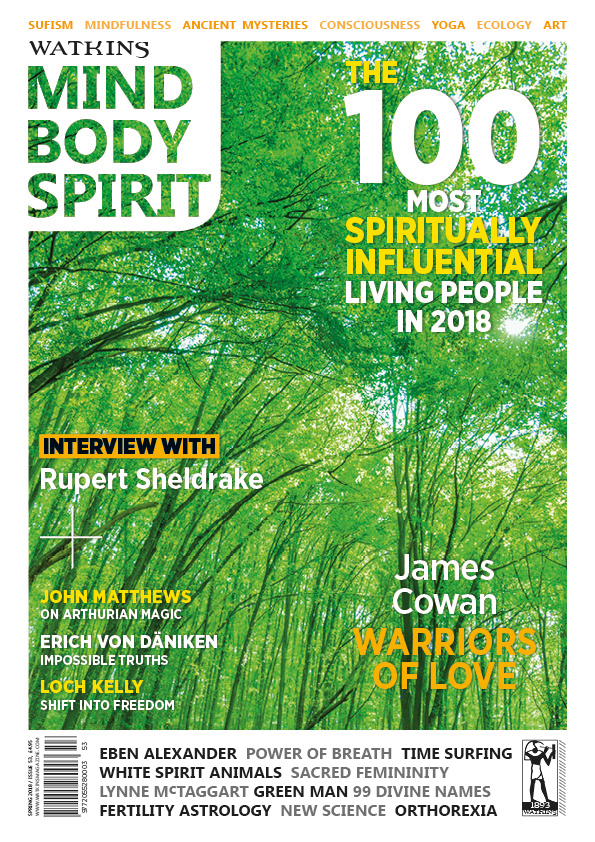

This article first appeared in Watkins Mind Body Spirit, issue 53.

Every one of us sooner or later walks through hell. The hell of being hurt, the hell of hurting another. The hell of cancer, the hell of a reluctant, thinking shovelful of earth upon the casket of someone we deeply loved. The hell of divorce, of a kid in trouble, of Alzheimer’s, of addiction, of stress, of aging; of knowing that this year, like any year, may be our last. We all walk through hell. The point is to not come out empty-handed. The point is to make your life worthy of your suffering.

To be human is to suffer, and there is profound power in the suffering we endure if we transform it into a more authentic, meaningful life. Pain is a great teacher, but the lessons do not come easily. I have had people whose spouses had affairs tell me that working through the infidelity brought them a renewed love and a renewed marriage, better and more real than before. I have also had people tell me just the opposite. “Do we love each other?” one woman asked me rhetorically. “Yes. Am I glad we stayed married? Sure. But it will never be the same, and it would have been much better if it had never happened.” Whenever I’m tempted to dismiss pain as merely a step toward enlightenment, I think about a friend of mine who had cancer three times and said to me from his hospital bed before he died, “This much character I don’t need!”

I do not intend to glorify suffering or suggest that the lessons we learn from pain are somehow worth the cost. But the truth is that most often for most people, real change is the result of real pain. More Beautiful than Before is about real pain in its many forms and the lessons it comes to teach.

As the senior rabbi of one of the world’s largest synagogues, I have witnessed a lot of pain. It’s my phone that rings when people’s bodies or lives fall apart. The couch in my office is often drenched with tears, and there are days when an entire box of tissues is gone by late afternoon. I have tried to help thousands of people face their emotional and physical pain, and after 27 years of listening, comforting, showing up, and holding them, I thought I knew a great deal about suffering. The truth is, it wasn’t until my own pain brought me to my knees that I could really understand the suffering of those who came to me wounded and afraid.

A few months after a frightening car accident from which I thought I had emerged physically unharmed, I was pulling into the garage at home when a herniated disc touched and burned a nerve in my spine. The pain was paralyzing. I could not step out of the car. The doctor said to call the paramedics. Instead of dialing 911, I used my upper body to drag my lower body inch by inch, writhing and screaming, across the oil-stained garage into the house, where I curled up and wept on the floor, fetal and begging for morphine. Through the seductive opioids, the surgery, more and more and more drugs, the exhaustion, the withdrawal, the depression, the fear, the bitterness of why me? why now? and the healing that followed, I learned a good deal more about pain, both physical and emotional, than a lifetime of witnessing others’ pain had taught me.

At first, I did not take my pain seriously. I took painkillers, tried to hide the fact that I wasn’t sleeping much, kept up my brutal pace at work, and grimaced whenever I stood up. After the surgery a woman who was a Temple trustee at the time called me and said, “You broke your back for the synagogue.” Her words shot through me. She was wrong from a medical standpoint, but she was right spiritually. I was ground down by years of carrying the suffering of others and the begging, pleasing, encouraging, and cheerleading that fundraising required when others refused to believe. So what did I do just 10 days after spinal surgery? I allowed a doctor to shoot me up so that I could walk back out onto the stage and play my part.

It was the High Holy Days—the 10 holiest days of the entire year for Jews, and the Super Bowl for rabbis, especially in my case and especially that year. We had just finished a two-year renovation of our historic 1,800-seat sanctuary, a magnificent place of prayer created in 1929 by movie moguls Louis B. Mayer, the Warner brothers, Carl Laemmle, and other famous Hollywood luminaries. The congregation had spent the two years of the renovation in temporary worship space, but this year we were coming home to a stunning, inspiring place of prayer, its 140-foot golden, green, and tan dome speckled with colors diffused through enormous deep blue and crimson stained-glass windows and bathed in soft white light from above by 30-foot brass chandeliers dangling from the dome like earrings on a queen. The total project cost for the sanctuary and the rest of the campus would be 200 million dollars, 150 million of which I had raised so far through countless conversations, dinners, events, and meetings over a period of 10 years. I didn’t really want to acknowledge it, but all that fund-raising, along with running such a large congregation with a staff of hundreds and 7,000 members, depleted me. I was spent and confused.

“You’ve got six hours,” the head of the hospital’s spinal team told me as he jabbed the needle in. “After that, you won’t be able to stand.” My wife was the only person to tell me I was wrong to be on the pulpit that night as the project I had worked so hard to make real was unveiled. She was the only one worried more about me than about the congregation’s expectations of me. Even I was not worried about me. If the pain was a relentless teacher, the student was a relentless denier.

I made it through the evening, but afterward I continued to suffer terribly for months, trapped in my old ways—always there for everyone, always punching above my weight, the hardest, the longest, and the fastest—I knew no other way. And then there were the drugs. I spiraled, like millions of others, into the lethargy and depression of steroids and opioids—the pain was dulled, but the pain was still in charge.

The Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan often repeated the aphorism that “we don’t know who discovered water, but it wasn’t the fish.” What he meant was that we are so close to our own lives, so immersed in our own reality, that we actually have the least perspective on it. Only when it’s hooked, thrashing in a net, gills gasping, and flailing for breath, only then does a fish discover water. So too with us—only when pain suddenly jerks us out of our otherwise ordinary life do we discover something powerful and true about ourselves. I have seen this up close thousands of times in hospital rooms, cemeteries, criminal courts, homes, and my office as others sat upon what I call my couch of tears, weeping from deep within. Through sickness we discover the blessing of health, through loss we discover the true depths of love, through foolishness we know maturity and wisdom. Pain shocks us and propels us from where we thought we were—who we thought we were—to something far more real and true. When pain visited me, I knew intellectually that I was not making history. I was not the first middle-aged man to herniate a disc. But pain is not a matter of intellect—it is a matter of the spirit and a matter of the soul.

It took years for me to appreciate pain’s victory. Now I am grateful for my defeat. It forced me to change my stubborn ways. It forced me to make peace with age, flesh, bone, decline, limitation, and the simple fact that we are all merely human. We can only do so much. Then we have to let go.

My pain forced me to stop many things. One of the first and most seemingly insignificant but symbolically powerful things I had to stop was my war with weeds. Yes . . . weeds. Ever since buying our current home 11 years earlier, I’d been obsessed with getting rid of the weeds on the large, very steep hill behind it. I wanted nothing but a blanket of perfect, dark-green ivy when I looked out my back windows. I tried sprays, potions, axes, shovels, a chainsaw, machetes, pitchforks, trimmers, loppers—you name it. For a decade, every few days I was up on that hill slipping, falling, cursing—bent over and at war with those weeds while my wife, Betsy, shook her head and futilely uttered a simple truth repeated by wives to their husbands for 5,000 years: “You know we could hire someone to do that.”

About a month after my spinal surgery, I emerged from the narcotic and steroidal haze just enough to walk the few steps to the back patio and lie on a lounge chair. That’s when I saw them: hundreds of tall, gangly weeds sprouting on the back hill—an insult to my infirmity. I could do nothing to combat this aggressive new crop of nature’s unceasing will.

Then I noticed something else: a group of tiny yellow birds perched atop those once-hated weeds. For weeks their singing kept me company each afternoon as I tried to heal in the warm sun. The weeds I had beaten back for years now attracted those delicate, little yellow birds. Pain cracks us open. It breaks us. But in the breaking, there is a new kind of wholeness that emerges. From my brokenness, a new, beautiful mantra emerged: weeds bring yellow birds.

More Beautiful than Before is a journey through pain in three stages: surviving, healing, and growing. It is an exploration of pain’s fierce, liberating, sorrowful, comforting, ugly, beautiful truths; the deepest truths. The truth that when we must endure, we can endure; that we can be good even when we cannot be happy; and that the sun rises no matter how dark the night. The people you will meet along the way, the ancient parables and scientific insights I share, my journey and the journeys I have walked hand-in-hand with so many others, will, I hope, help move you from pain to wisdom. They say every preacher has one sermon, one truth that he delivers 100 different ways. Mine is to inspire in us all a life worthy of our suffering: a life gentler, wiser, and more beautiful than before.

Meet the author: Rabbi Steven Z. Leder is the Senior Rabbi of Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles and the author of The Extraordinary Nature of Ordinary Things and More Money than God. He has studied at Northwestern University; Trinity College, Oxford; and Hebrew Union College. Newsweek magazine named him one of the ten most influential rabbis in America. He lives with his family in Los Angeles.