Watkins Mind Body Spirit shares a Q&A with Claire Willis, co-author of Opening to Grief (Red Wheel Weiser, publishing 25 October 2020).

Q: What do you mean when you use the word grief?

A: We often think we know what grief is, but it’s actually hard to describe. Perhaps the first thing to say is that grief is a normal and natural response to a major loss that occurs when an important relationship is ruptured. And it is, for most people, immensely painful.

As humans there are obvious losses that will come to most of us – parents, siblings, friends, and relatives. There are also more invisible losses that some of us may experience, losses that are less culturally recognized, such as infertility, the loss of a beloved pet, the loss of a home, innocence, health, or the loss of capacities as we age.

Then there are the losses that I call macro losses, the degradation of the environment, economic chaos, or the losses caused by war. While we may not know the people involved in these catastrophes, there is still a rupture of relationship among humans. Most recently, the glaring exposure of racism, police brutality, and systemic oppression of African-Americans across the US has become a source of deep grief and outrage to all people of conscience. African Americans and people of color have been traumatized physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually for centuries. We grieve our complicity.

Q: How does grief manifest in our lives?

A: Grief may manifest in intense physical sensations, such as loss of appetite, a feeling of anxiety, unrest or restlessness in the body, or a feeling of overwhelming exhaustion. Grief affects emotions, appearing as irritation, sadness, anger, depression, or numbness. And grief affects cognition, too. Many people experience difficulties concentrating, remembering things, or even thinking straight.

Q: How do we think about grief?

A: Most of us initially think of grief as sadness, but grief includes other more positive feelings and mind states, too. Over the years, I have come to trust the full expression of grief, because with time, grief can also include feelings such as relief, joy, and gratitude. This is especially true for people who have lost someone who has suffered a protracted illness.

Grief itself is big enough to hold both positive and negative qualities and experiences. Grief, for all its pain, is also an expression of love for what and whom we have lost. Kahlil Gibran wrote in The Prophet, “The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.”

Q: Is there a timetable or path of grief, so people know what to expect?

A: No, there really isn’t a timetable or a single path. Grief takes as long as it takes. There are as many different expressions of grief as there are people who are grieving.

I spend a lot of time in my clinical work normalizing whatever someone’s experience is, because there is no right way to grieve. I always say that grieving is a little bit like looking at the sun. We look at the sun, we turn away, we look, and turn away. We can’t stare at it, because it would burn our eyes. We titrate it in whatever ways we are able. Some people over-work, exercise vigorously, eat a bit more than usual, or have a second or third glass of wine. We all find different ways of bearing the impact of losses.

What is most important, though, is to avoid numbing out and to find your own particular ways of holding and being with loss. For some, it is spending time in nature. For others, art, meditation, or talking with friends, family, or joining a support group may help you make sense of your experience.

Q: I have read in various places about the stages of grief. Can you comment on that?

A: Most people are thinking of the work of Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who used the idea of stages in describing the emotional process patients go through as they come to terms with death. Her five-stage linear model includes denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Kübler-Ross also developed her theory to address grief, but she did not intend to assert that everyone goes through grief in predictable stages. Still, her research has been interpreted and misunderstood in these ways and has profoundly influenced popular culture.

We now know that grief does not travel in a linear, predictable way. People who are grieving may experience some of the stages in her five-step model; for example, denial or acceptance. But other steps are not so predictable, or may not occur at all.

I have seen too many people in bereavement groups criticize themselves because their grief does not resemble Dr. Kübler-Ross’ linear path. I often hear, “I am not grieving right.” One of the messages I try to convey is that there are as many different expressions of grief as there are folks who are grieving.

I had a great example of this point in one of my groups. One person joined two weeks after he lost his partner, stayed two weeks, and then told the group he felt he was over his grief because he had anticipated the loss of his wife for so long. Another man joined the same group three years after his wife died, because he did not feel he had allowed enough space in his life to grieve.

Q: What would you say to someone who says that they will never get over losing someone they loved?

A: I would say that is true. You may never get over losing the person you love. But that may be welcome news, since you may keep memories of the person you lost in ways that will comfort and sustain you. It’s important to allow and feel the pain of missing someone or something you loved, to let the pain be the pain, not hoping that it will disappear, but trusting that at some point it will fit into your life. Grief is natural and will eventually shape and be shaped by your life.

I recently heard an analogy between the course of grief and the way a broken bone heals. After a bone breaks, there is sharp pain. Surgery, rest, and physical therapy eventually help heal the bone. But even after the bone heals, it may still ache on rainy days.

Q: Can a person get ‘stuck’ in the grieving process?

A: The idea of being stuck is really subjective. Being stuck may manifest as a hardening of the heart, or a constant flooding of feelings. I think that someone is likely ‘stuck’ if they use the same maladaptive patterns over and over in a way that is hurtful to themselves or those around them. Examples would be self-medicating for a prolonged period of time with pills, alcohol, food, excessive exercise, or too much work.

There are certain conditions that may make it more likely that someone gets stuck. Perhaps the death itself was complicated — either violent, sudden, or a suicide. Perhaps a family member did not have an advanced directive and someone had to make a decision without any input from their loved one; this situation is likely to cause inner conflict and guilt for family members. Perhaps there was an exchange of very angry words at the end of a partner’s life, and the survivor is perseverating over the last words they exchanged. Often people with prior psychological conditions find grief very difficult.

A common way of staying stuck occurs when you do not allow yourself to feel your feelings. There’s an expression: What we don’t feel, we cannot heal. Or as one of my teachers used to say, “Try to turn into the skid.” By using energy to protect ourselves from grief, we may get sick and have fewer resources to connect with ourselves and others.

Turning toward our grief can be an expression of love. Of course, we have to titrate grief in gentle ways, so that it does not overwhelm us.

Q: What advice do you give to people who ask, “Will it always feel this painful?”

A: For most folks the answer is “No, it will not always feel this way.” The passage of time for most people is some help. But time by itself is not the answer. It’s how we spend the time. As Joanne Cacciatore writes in her beautiful book, Bearing the Unbearable, we need to exercise our “grief-bearing muscles” by being with the pain. With the passage of time, you move further away from the loss itself. With time and stretching our muscles, we have an opportunity to integrate new resources into our life, so that the grief is less in the foreground and more in the background. With these additional resources, the sharp pain of grief may move toward more of a soft ache.

Q: Both you and your co-author, Marnie Crawford Samuelson, are practicing Buddhists. Opening to Grief offers several meditations; how can a mindfulness practice help someone through grief?

A: We introduce you to some basic ideas of being mindful: paying a kind of warm-hearted attention to life as it unfolds in the present moment; being aware of your thoughts and feelings without getting caught up in or judging them; relaxing and settling into calm and stillness; and feeling grateful for the life that is yours. We show you how it is possible to lean toward and stay with raw, uncomfortable feelings of grief, even when you feel overwhelmed and want to run away.

One way a mindfulness practice helps is by drawing your attention to your breathing. This is a way of calming your body and mind. When we are grieving, we may be overwhelmed by fears of the future, or memories of the past. The essential quality of mindfulness is about living in the present moment. Being mindful reduces stress, increases our emotional resilience to difficulties, and helps us cultivate more steadiness.

Q: When you are grieving, how does spending time in nature help?

A: When you are grieving, spending time in nature is healing for many of us. We all enjoy nature for our own reasons. Some of us love solitude. Instead of feeling lonely, we find ourselves in nature. Some feel connected being in an environment larger than our selves.

When we spend time in restorative places, it becomes effortless to watch leaves floating down from trees, notice a reflection of the sky in a puddle, or hear a bird call. These environments draw us in without asking us to focus on anything special. There’s nothing to do. When we return home, we feel refreshed.

Across Canada, people have formed walking groups to help with grief. They gather, stand together, and share memories. Some cry. No one tries to fix anything. They just meet and listen to each other. And then they walk together, one step at a time.

Q: You mention that some people who are grieving find solace in writing. How does this help?

A: We show you how to get started, even if you’ve been told you’re not a writer, or you don’t feel confident that you can find the right words, or craft a perfect sentence. We explore how writing can help you make sense of what has happened. Writing can often become a way to create structure around an experience that feels chaotic. Some people have found that by setting aside a time to just remember and write about their loved one or pet or whatever loss they are holding has offered them solace. It can be a quiet and settled way to be with your grief. What’s important is the experience or process of writing, rather than the quality of what you create.

Q: In your book, you explore how making things helps some people heal after a profound loss. How do you suggest someone begin, especially if they feel that they are not creative?

A: We draw upon the healing powers of making art, for both amateurs and experienced practitioners. We encourage you to embrace “beginner’s mind,” let go of judgments and self-criticism, and plunge in. When we were young, we all did art pretty freely and without any self-consciousness. At some point we lost confidence in our creativity. But we did not lose our creativity. It just got buried.

It is a good time while we grieve to reclaim our creative juices, which can be a source of solace.

Try putting your emphasis on the process: can you find some delight in making something and forget about how it turns out?

“…when you notice something that is beautiful or loving and draws your attention, linger with it and let your mind and heart stay with it for at least 20 -30 seconds”

Q: How does someone know whether they are grieving or depressed, and whether to consult with a mental health professional?

A: Grief is characterized by a complicated mix of emotions including acute sorrow and is a normal response to major loss such as death, disease, divorce, or violence in the world. Grief comes and goes with intensity, so that people often find they can experience moments of relief and joy. With depression there is a sense of “suck-the-pleasure-out-of-everything that permeates your days. Some behaviors that would immediately signal a need for help would include thoughts of suicide, isolating, and preoccupation with the deceased.

If feelings of sadness or hopelessness are persistent and blanket everything, that may indicate depression, rather than simple or even more complicated grief. If you feel you might be depressed, it would be wise to consult with a mental health or medical professional.

Q: Since the COVID-19 pandemic, many people report remembering losses from long ago. Why would these memories be arising now?

A: Sometimes memories of earlier losses emerge because you were not able to grieve them fully when they occurred. Perhaps you were too busy coping with life. Or maybe you didn’t give yourself permission to grieve, or you experienced multiple losses in a short period of time, and you weren’t able to grieve them all. Whatever the reasons, losses that we have not processed do return and ask for our attention. A major event such as a pandemic may certainly create an opening for old griefs, as well as new losses, to come roaring in.

Grief can be like a very messy room in our house. It’s best to enter slowly and pick up one item at a time. If we try to face and take in the entire room at once, we can become overwhelmed and paralyzed by the magnitude and intensity of our feelings and by all the rich “stuff” that’s there.

Q: In these unprecedented times, many people are sensitized to losses and inequities in our society that have actually always been here, but are now revealed more starkly. These include inequities and disparities in the health care system, the impact of systemic racism, a growing gap between the rich and poor across the country, and massive losses due to global warming. How do we begin to hold all this searing grief, as it tumbles in all at once?

A: The pandemic has peeled blinders off our eyes, and so have the traumatic killings of people of color by police. People of conscience can’t turn away, now that we see systemic and global injustices.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has also catalyzed many unexpected acts of kindness, generosity, and love.

While it is natural for our minds to turn toward what’s difficult and painful, it is important to also linger with and take in positive experiences of joy and harmony. Researcher, psychologist and author Rick Hanson suggests that when you notice something that is beautiful or loving and draws your attention, linger with it and let your mind and heart stay with it for at least 20 -30 seconds. Allow this basic goodness to wash over you. See whether this practice helps you develop resilience and strength, so that you are better able to be with and bear suffering that is present everywhere.

Q: What advice do you have for people who are suffering from grief?

A: First, it’s important for people to be patient with themselves. I encourage people to offer themselves great kindness and compassion, as they learn to trust their own compass and find their own true north.

Though this may be hard to believe or accept, especially when grief is new and raw, grief is an invitation to grow and eventually to find meaning in suffering and experiences of loss that you did not ask for and do not want. A heart that is broken open offers a precious gift—a chance to become more authentic with yourself and with others. In the case of the pandemic, it is a wake-up call to attend to the health of our planet and consider how we might live differently, and what we can do to help repair the rupture in our home.

Find out more

Claire B. Willis is a clinical social worker who has worked in the fields of oncology and bereavement for more than 20 years. A cofounder of the Boston non-profit Facing Cancer Together, Willis has led bereavement, end-of-life, support, and therapeutic writing groups. She maintains a private practice in Brookline, Massachusetts. As a lay Buddhist chaplain, she focuses on contemplative practices for end-of-life care. For the past five years, she has been a student of Koshin Paley Ellison, a founding teacher at the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care.

Video: Grieving for the Loss of a Pet

Video: Mental Health and Disenfranchised or Invisible Grief

Bookshelf

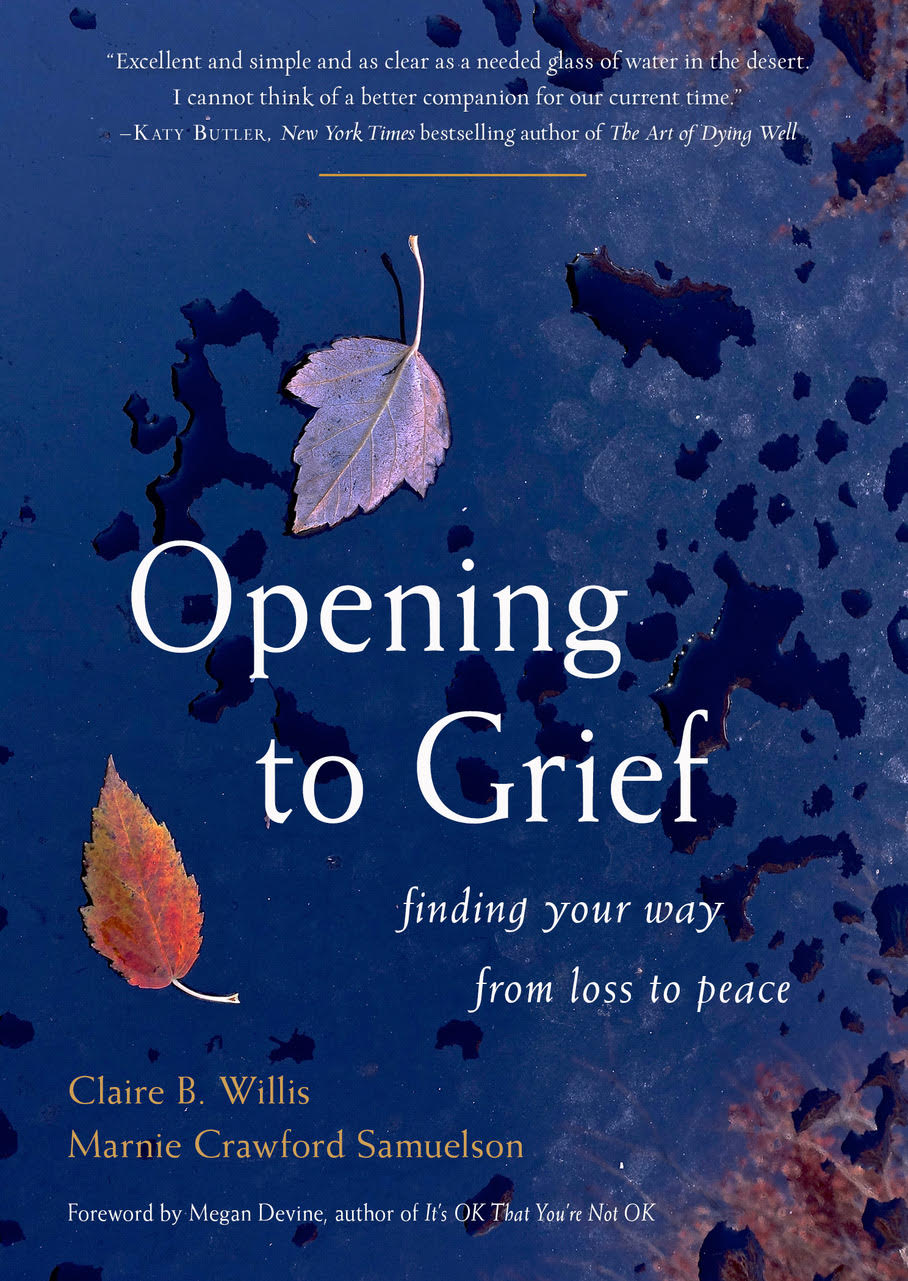

Opening to Grief: Finding Your Way from Loss to Peace by Claire Willis, published by Red Wheel Weiser, RRP £13.99