by Stephen Skinner

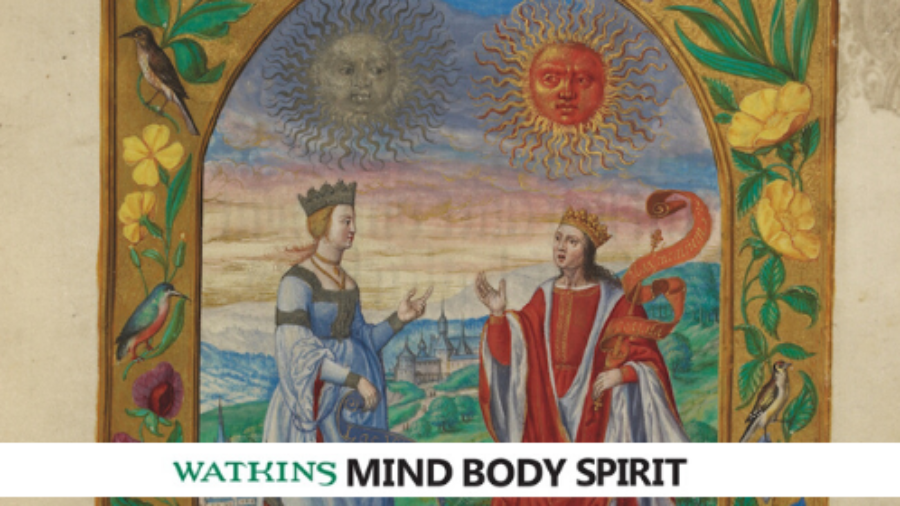

Anyone who has ever been interested in alchemy will have come across one or more pages from this very beautiful and enigmatic manuscript dating from 1582. The Splendor Solis contains 22 images which relate to the transmutation of base metals into gold.

It explores this process, in four different sequences, using the seven classical planets; the physical colour changes; and the story of the chemical wedding between the solar king and the luna queen. The fourth and last sequence portrays alchemy as ‘child’s play’ and ‘women’s work’ as its processes parallel the washing and cooking of the ore in the alchemist’s effort to refine it. These images also imply that basically the process is not difficult or complicated. Indeed, perhaps the most difficult choice is deciding what is the prima materia, or the starting point. Alchemists have tried many things as a starting point including egg yolks, lead or even mud. Splendor Solis makes it abundantly clear that the starting point is a mineral, most likely an ore or maybe a regulus.

The text, which has been newly translated from the German by Joscelyn Godwin, supersedes other previous but less accurate and complete translations. I supply a commentary on the meaning and symbolism, interpreting the images as well as the strange Latin tags that appear in some of the pictures, and relating these figures to alchemic symbology and process. Rafal Prinke gives the history and origins of the text, tracing its evolution through manuscript and early printed forms. There is no doubt that this particular 1582 manuscript forms the high point of its evolution. Finally, Georgiana Hedesan relates the work to Paracelsus and his school. Of all the illustrated alchemic texts perhaps the best known is Splendor Solis, and yet there are no editions of it offering both an accurate full English translation and reproductions of all its plates in colour at a reasonable price, until the present edition.

The intention of the original author of Splendor Solis was to describe the physical pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone and its use in metallic transmutation, rather than the Jungian psychological interpretations which were imposed on it in the 20th century. While researching the subconscious, Carl Gustav Jung became aware of the fact that the archetypal images that his patients encountered had also arisen in other fields and been noted by other thinkers in past times who were working in entirely different spaces. Alchemy was one such field that appeared to parallel these images. There is no mystery here, as the fact is that these so-called archetypal images were part of our culture, the shared art, images and stories of all European culture.

The alchemists were primarily concerned with the creation of the Stone of the Philosophers, the Universal Medicine and the transmutation of base metals into gold. They were not interested in using these formulae as a form of depth psychology and are more likely to have visited their priest if they had any spiritual concerns. Projecting the methods of psychotherapy backwards onto the thinking of the alchemists is completely anachronistic.

Artists since ancient times included these images in their work, and in the illustrations they made for mythological paintings and alchemical emblems. The reason for much of the similarity is that artists used standard images which came from emblem books, which were used by artists to portray standard themes like the gods of Greece and Rome. Nowadays artists just paint whatever they wish and do not use these emblem books to guide them, so as a result modern art is no longer full of archetypal images. The alchemists were aware of these images and used them to get across their message. The gods of classical mythology have helped shape the culture of the West, and so it is not surprising that such images also surfaced in the dreams of Jung’s patients. But this does not mean that you can interpret alchemical texts using Jungian psychology, as no 16th century alchemist would have thought about it like this. Additionally, none of these sequences relate to the Tarot despite earlier commentators, like ‘J.K.’ attempting to force them into this mould.

Not only alchemists but many lay persons assumed that gold was slowly formed in rock strata over many thousands of years, because both pure gold and gold ore were found together in mines – it was considered obvious that eventually one turned into the other. Alchemists thought that with the right ‘cooking’ conditions they could speed up the development of metal ores into metallic gold; it was just a question of speeding up the natural processes of Nature. In the book, the commentary leads the reader through the various alchemical stages, explaining the sequence of colour changes that indicated the process was proceeding correctly.

An intriguing note found at the front of the manuscript in pencil reports that “Baron Boetcher of Dresden is said to have made (transformed) many hundred weight of Gold according to the method of this Book – He learned the Art of an Apothecary in Berlin.” Boetcher was just one of hundreds who attempted this transformation, and if you believe this note, succeeded.

Belief in the viability of such transmutation has perished in the last three centuries, but the appeal of the vibrant images in this manuscript remains. Just thumbing through this book, or reading the commentary, stir thoughts and feelings that modern man seldom experiences any more.

Find out more:

Dr. Stephen Skinner is an expert in 15th to 18th century magic manuscripts and the author of more than 40 books on Western esoteric traditions. He was awarded a PhD in Classics by the University of Newcastle for his research into the Greek text of the magical papyri (PGM) and its connection with the Latin grimoires. The first part of this thesis has been published as Techniques of Graeco-Egyptian Magic, the second part as Techniques of Solomonic Magic. He lives in Singapore.