by Matthew Juksan Sullivan

Zen Master Daowu and his student Jianyuan made a condolence call to a layman’s family. Jianyuan tapped the coffin and said, “Alive or dead?” Daowu said, “I won’t say alive and I won’t say dead.” Jianyuan said, “Why won’t you say?” Daowu said, “I won’t say.”

– – Zen Buddhist Koan from The Blue Cliff Record

My father died in July. A progressive disease blighted his last years. As he planned, he passed away with the help of medically assisted dying. This meant we were living with the presence of his death for a long time before he actually died. It was a long wait, and then it wasn’t. All of a sudden, there he lay on the old leather couch. Our small family surrounded him, and I was touching his hand as the various injections darkened his senses and stopped his heart.

A few weeks after Dad died, I lost my dog. He had to be re-homed because he was an incurable biter. It feels unseemly to mention my dog in the same breath as my father. My father was a person in full. He raised me with love, became my friend as I grew into an adult, and introduced me to many of the things I treasure as a man, like meditation and mindfulness. My dog, on the other hand, was usually aloof and sometimes aggressive. And I only had him for a year. Not only that, my dog isn’t even dead. In fact, he’s flourishing, since he’s now living with a trainer who can meet his needs more fully than I ever could.

Yet I sobbed like a child for my dog and remained calm at all times with respect to my Dad’s death. How can that be?

At first I thought my different reactions were a matter of shock, or perhaps a displacement of anguish. I know enough about grieving to know it can be a complex process stirring unpredictable emotions, most of which won’t fit in the box of appropriate sadness. However, as the days and weeks stretched into seasons, my feelings didn’t change.

My dog was gone, and that’s why I keened for him. No more could I touch his sleek body, walk him before breakfast, or brush his teeth. The situation with my father was different. I had never brushed his teeth. Yet his presence in my every-day life was an ambient music. There is the oak table he made for my living room, there is the books we exchanged back-and-forth, and there is the loping gait that I inherited from him. None of these things disappeared after he died. He might be dead, but he wasn’t particularly absent.

When I was a young man, I spent a year as the cook at a Tibetan Buddhist retreat center on a small island off the coast of British Columbia. One morning, one of the long-term retreatants—a man who had spent years in meditation—demanded that I bake a cake for dessert after lunch. Being young and somewhat attached to monastic regularity, I decided not to comply because it was not part of the menu plan for that week. Plus, I was new to cooking and was a little scared of producing a wet or lopsided mess.

When no cake was forthcoming at lunch, the retreatant stomped into the kitchen and told me off with gusto. Looking back on it now, I have nothing but sympathy for him. After having completed a few long retreats myself, I know how essential certain foods can seem when everything else around you is silence and austerity. At the time, however, I was stunned that someone who had spent so much time meditating could be so angry at not getting cake.

With her usual grace, the Lama presiding over the retreat center intervened in the dispute. When we were alone, I asked Lama Tara why the man’s years of Buddhist practice had not moderated his temper, and she told me something that I have thought about often in the intervening 25 years. “Well Matthew,” she said, “a lifetime of meditation is a funny thing. You can watch your house burn down and take it in stride. But then someone gets your order wrong at the restaurant and you have a meltdown.”

I often revisit Lama Tara’s words because, after my own lifetime of meditation, I frequently experience meltdowns at small things. The practice of mindfulness hasn’t turned me into an impervious gold statute. Rather, by enhancing my self-awareness, it has taken my inherent sensitivity and rendered it more tender. I suspect a lot of other meditators have the same experience.

I suppose I’m lucky that I haven’t often encountered the other half of Lama Tara’s equation. I have not had many experiences like seeing my house burn down so that I could test whether I would “take it in stride.” That is, I didn’t have many such experiences until Dad died.

In Buddhism there is a lot of talk about how life and death are not so different. The dharma tells us that the true self is much bigger and more expansive than the narrow confines of the conscious ego. Our subjective consciousness might cease at death, but in some ways, it was always the least interesting thing about us. The true self lives on because it is diffused throughout all those things that ceaselessly interpenetrate the lives of those around us: the tables we make, the books we exchange, the traits we bequeath. We are like waves in a vast ocean. One wave crashes into the shore, but it’s substance never vanishes because it returns to yet more waves.

I’ve taught and written about these ideas for many years now, but I guess I always figured that when it came to the deaths of those I love most, they wouldn’t actually be much help. I’ve been happy to discover that I was wrong.

My Dad’s death has made me realize that a lifetime of meditation really does do funny things to you. I miss seeing my Dad’s smile or asking about his latest one-dollar wager with his neighbor. But I don’t mourn him because I don’t know what there is to mourn. To my own surprise, I find that I just don’t believe in his death. Or perhaps to put it more accurately, I don’t believe that much has changed since he died. He’s no more gone out of my life than the oxygen in my lungs.

Perhaps the greatest gift that mindfulness can give us is a capacity to escape unhelpful dualities. By helping us to let go of our thoughts, meditation teaches us that we don’t need to cling to either/or choices like “good or bad,” “desirable or undesirable” or even “life or death.” As Zen Master Daowu said over 1000 years ago, “I won’t say alive and I won’t say dead.” In the space of meditation, there’s a middle way where we can embrace wordless mystery.

That’s where I am now. And Dad is here with me.

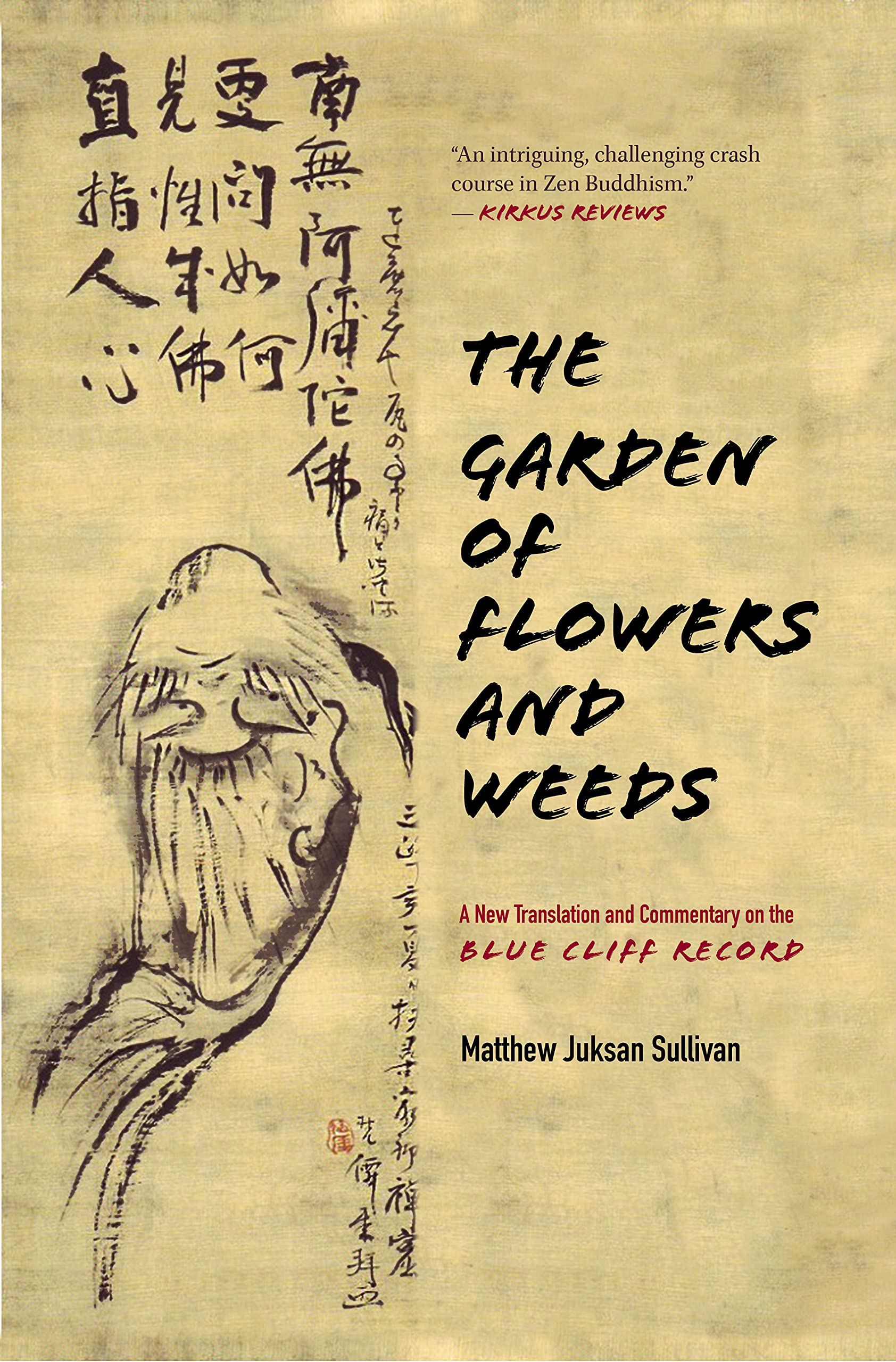

Matthew Juksan Sullivan was ordained at the Nine Mountains Zen Gate Society as a Dharma Teacher in 2006 and a Zen Master in 2013. His first book, The Garden of Flowers and Weeds: A New Translation and Commentary on the Blue Cliff Record (2020), won a gold Nautilus Award, a top prize from Bookfest’s International Book Awards and a silver Benjamin Franklin Award.

On the web

Bookshelf

THE GARDEN OF FLOWERS AND WEEDS: A NEW TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY ON THE BLUE CLIFF RECORD BY MATTHEW JUKSAN SULLIVAN, published by Monkfish, hardback (400 pages).